The Advantages of Community-Based Sports Promotion

Masafumi Izumi has been involved in the management of many major sports organizations, including the Japan Swimming Federation, Japan Amateur Sports Association (now Japan Sport Association), and Japanese Olympic Committee. As Japan faces serious demographic challenges due to a declining birthrate and dwindling population, he believes that sports can play a bigger role in promoting youth development in the community.

As vice-president and executive managing director of the Japan Sport Association, Masafumi Izumi actively promotes children’s participation in junior sports. ©Photo Kishimoto

“For years, schools have played a central role in promoting sports participation in Japan,” Izumi notes, “but with fewer children and an overburdened teaching staff, many are having a harder time offering a broad array of extracurricular athletic programs. The responsibility needs to be shouldered by such other groups as junior sports clubs belonging to the Japan Junior Sport Association and comprehensive community sports clubs.”

Indeed, according to a 2017 survey, the share belonging to a school sports club was 65.7% for middle school students and 48.1% for high school students.

“One drawback of a school-based sports program is the discontinuity kids experience when they move from elementary to middle and then to high school,” Izumi points out. “This can be mitigated when sports education is based instead in the community. It’ll also allow children to try many different sports while they’re young and then choose the one that best suits them. This might also be a more efficient approach of identifying and developing competitive athletes.

School-based programs should be augmented with those offered by junior and community sports clubs, Izumi believes, to ensure that sports continue to play a key role in youth development. ©Photo Kishimoto

“That said, there are many benefits of pursuing club activities at schools, so I’m not advocating they be scrapped. Perhaps one option would be to offer an hour of after-school club activities so students can play with their friends, after which they can participate in a different sport in a program offered by a junior or comprehensive community sports club—perhaps even at the same school gym. This will enable the effective use of school gymnasiums and give kids exposure to different instructors and coaches, helping circumvent the problem of power harassment that could emerge when kids are in the hands of a single coach for many hours.”

Teaching Inclusion from an Early Age

After working at a maritime shipping company for over 40 years, Yasushi Yamawaki has become one of Japan’s top para-sports officials, serving concurrently as a member of the International Paralympic Committee Governing Board, president of the Japanese Paralympic Committee, vice president of the Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games, and chairman of the Nippon Foundation Paralympic Support Center.

“Most people with disabilities don’t consider themselves lacking in any way,” Yamawaki asserts. “A ‘disability’ is a label society has created that says more about the observer than the observed. Paralympian Jun’ichi Kawai has emphatically stated that his visual impairment may be an inconvenience but doesn’t make him unhappy. I may not be able to see, he says, but I’m otherwise perfectly healthy, both in body and spirit. I think most para-athletes feel the same way. They’ve been able to work around their challenges and live as fully as anyone else.”

After becoming a board member of the Japanese Para-Sports Association, Yamawaki has devoted his energies to realizing the association’s goal of building a vibrant, coexistence society.

It was from personal experience that Yasushi Yamawaki (shown with para-alpine skiing gold medalist Takeshi Suzuki) realized that the feats of para-athletes could become a key factor in building a vibrant, coexistence society. ©Photo Kishimoto

“The first step in getting people to recognize the need for greater social inclusion and achieving a vibrant, coexistence society was to focus on the athletes engaged in para-sports. There’s an aura of fun and excitement about para-sports that attracts people regardless of their political or religious orientations. Just watching para-athletes perform is enough to produce change in the way people think.”

Another area of Yamawaki’s interest is promoting para-sports among schoolchildren as part of their physical education. “Young kids are so receptive. They don’t need an elaborate explanation; they can ‘get it’ just by watching, and this can make a really deep impression on them. If they realize one can lead a perfectly happy and fulfilling life even with a disability, they’ll talk to their parents about it. When we think of education, we usually imagine adults teaching children, but when it comes to para-sports, I’ve found that the reverse is often more effective. We need to focus our efforts on raising children to be without prejudice so they can build a more inclusive society in the future.”

The Nippon Foundation Paralympic Support Center, which Yamawaki chairs, has been conducting a program since 2016 under which para-athletes visit schools throughout Japan to lead hands-on classes on para-sports. ©The Nippon Foundation Paralympic Support Center

Developing Global Sports Leaders

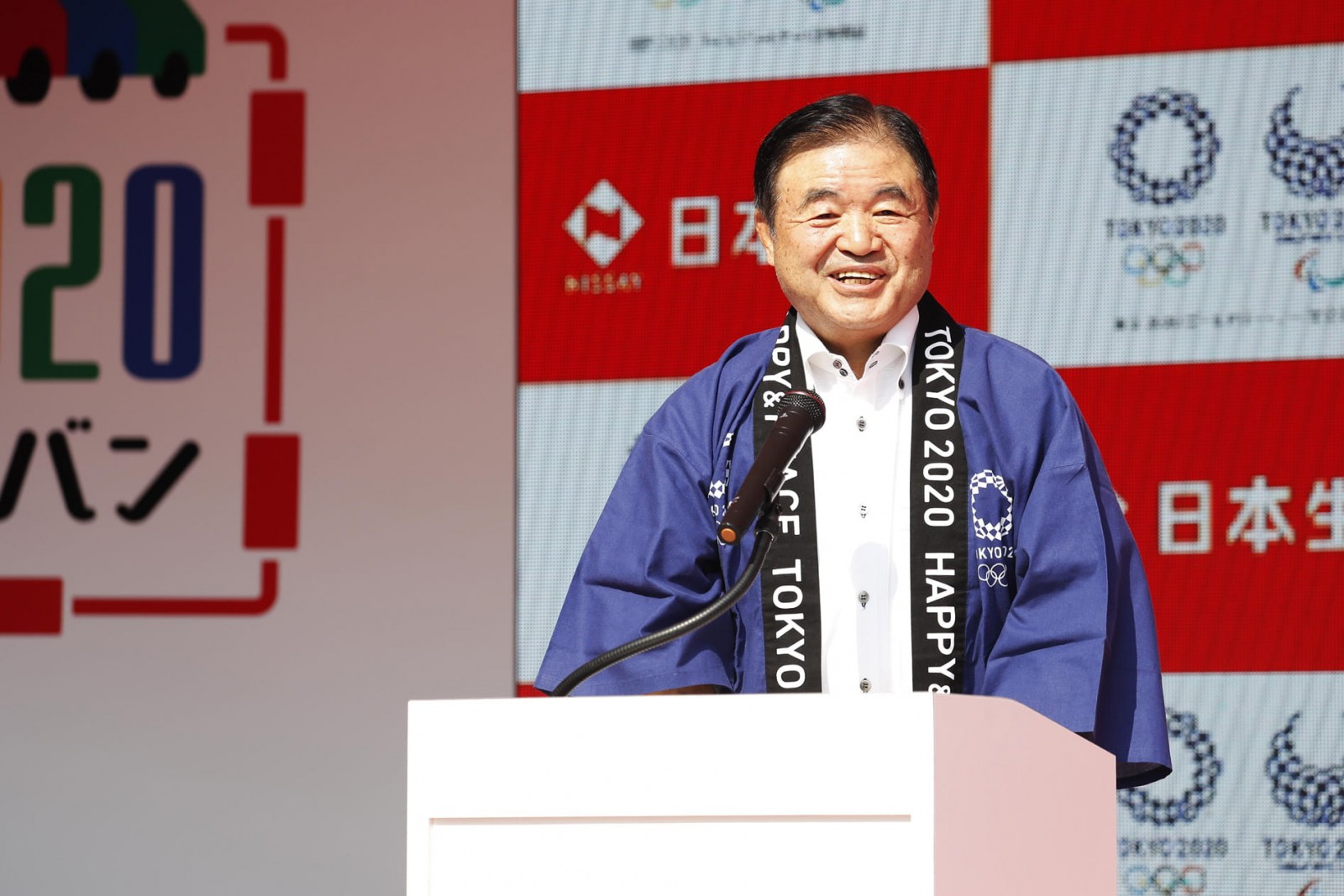

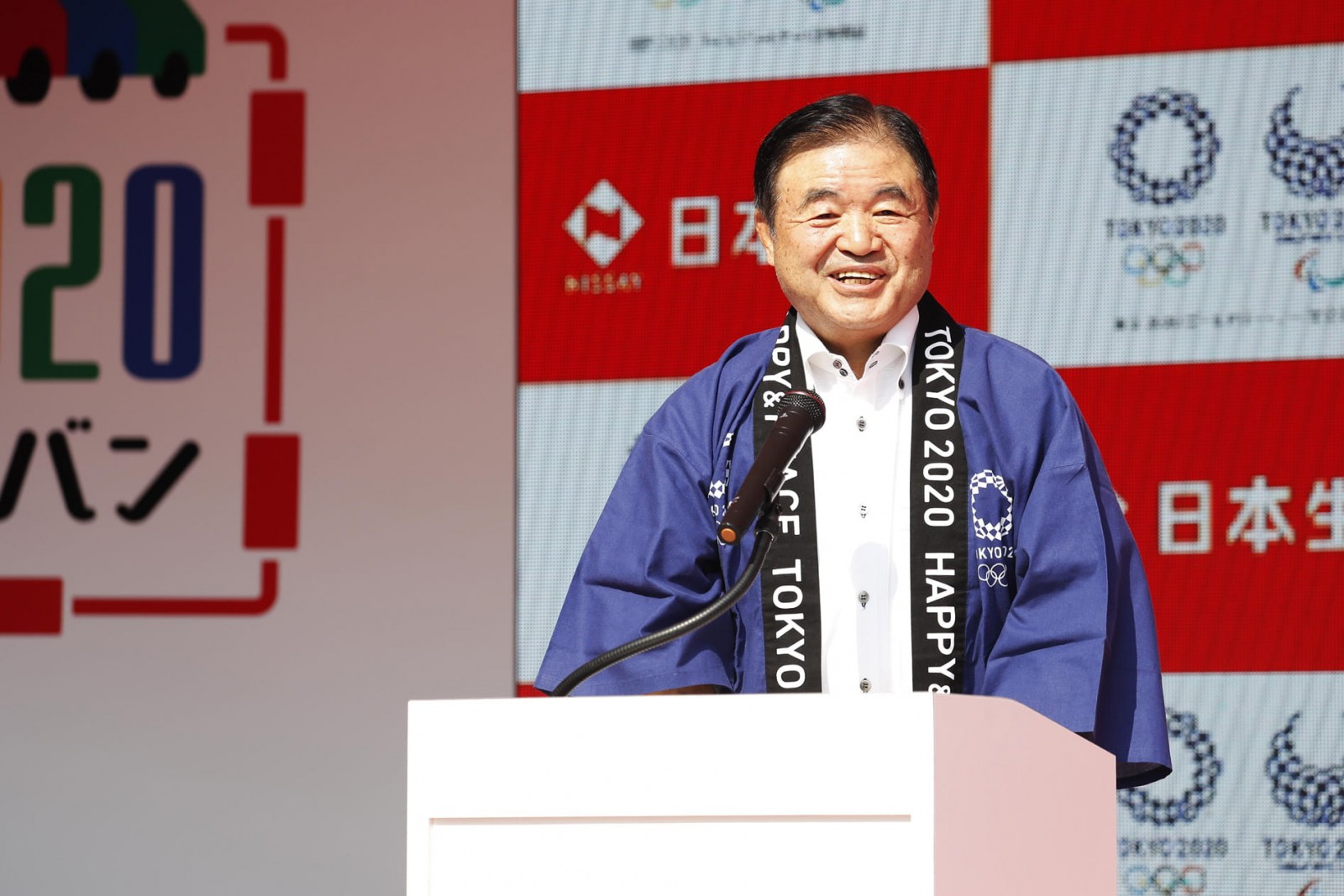

Diet member Toshiaki Endo is a former minister in charge of the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games and was recently appointed chair of the Liberal Democratic Party Election Strategy Committee. As a politician, he helped introduce a sports promotion lottery in 2001 to provide financial support for various sports organizations and enact the Basic Act on Sports in 2011. His views on sports were shaped by an unforgettable encounter with a university instructor.

Toshiaki Endo, who served as vice-president of the Tokyo 2020 Organizing Committee, is a national politician strongly committed to sports promotion. ©Photo Kishimoto

“Hiroki Kuwabara taught physical ed at Chuo University, where I played rugby,” recounts Endo. “He took issue with the harsh, punishing training rugby players were forced to go through and established Kurumi Club in 1965 to explore more enjoyable alternatives. He felt there’s no need for sports instructors to be tough on the players or to force them to practice for no good reason. Students, on their part, have adhered to a highly rigid, age-based hierarchy, which, he believed, ran counter to the egalitarian nature of sports. What’s the point of playing, he’d say, if you’re not going to have fun at it?

“I, too, hope to communicate how enjoyable sports can be and how easy it is to participate. After all, if it’s not fun, how can sports contribute to people’s health, regional development, or international goodwill? My personal goal is to employ sports in a variety of ways to benefit society, including in unique and unorthodox ways.”

Hiroki Kuwabara, seated center, was Endo’s mentor at Chuo University and created the Kurumi Club to explore more enjoyable approaches to playing rugby. (Image via Kurumi Club)

This is a goal that Endo has actively sought to fulfill as a politician. He has devoted his energies to promoting sports in public policy, launching a study group on sports policy while serving as senior vice-minister of education, culture, sports, science, and technology.

“One of the issues we examined in the study group was the decline in Japan’s competitiveness at international sporting events. We found that this was partly the result of businesses withdrawing their sponsorship of sports teams as the Japanese economy stagnated. Another factor was the lack of government support, with many coaches having to volunteer their time to developing the next generation of competitors. It was with the aim of strengthening public support that we began work on drafting the Basic Act on Sports and on establishing the Sports Agency to implement sports policy.

“I also launched a project with my Diet colleagues to develop sports leaders not just for organizations in Japan but also worldwide. There aren’t too many international bodies with Japanese presidents or vice-presidents. And I feel that Japan’s sports culture will continue to be underrepresented unless we can enhance Japan’s international presence at the leadership level.”

Comments by the speakers translated from excerpts of separate interviews conducted in Japanese on August 20, 2020 (Masafumi Izumi), February 2, 2016 (Yasushi Yamawaki), and August 1, 2019 (Toshiaki Endo).