Judo as an International Sport

Judo became an official Olympic event at the 1964 Games in Tokyo, after which it was long dominated by Japan. Other countries began winning the gold medal in a growing number of weight divisions from the 1988 Games in Seoul, and in 2012, at the London Games, the Japanese men’s team came away without a single judo gold.

Kosei Inoue, the under-100-kg-class gold medalist at the 2000 Sydney Games, was named head coach of the national team following the disappointing showing in London. He had honed his international coaching skills during the two years he spent in Britain following his retirement from competition, and he now looks forward to enhancing the image of judo and Japan at the Tokyo Games.

KOSEI INOUE: The biggest thing I learned during my years abroad was how little I knew about the world. I don’t mean that just in a negative way. It wasn’t that I became despondent. If anything, I was filled with a sense of wonder and excitement about all the things I could still absorb and the potential for personal growth.

I realized right away that foreign students won’t heed any advice that they don’t understand, even if it comes from a world champion. But once they do understand it, they’ll work really hard and be able to master it fairly quickly. In Japan, students initially do exactly as they’re told by their teachers and only later do they acquire an understanding of why things are done a certain way. I’m not saying one is better than the other, but unless you have a good enough grasp of what you’re doing to be able to explain it to others, progress is likely to be slow.

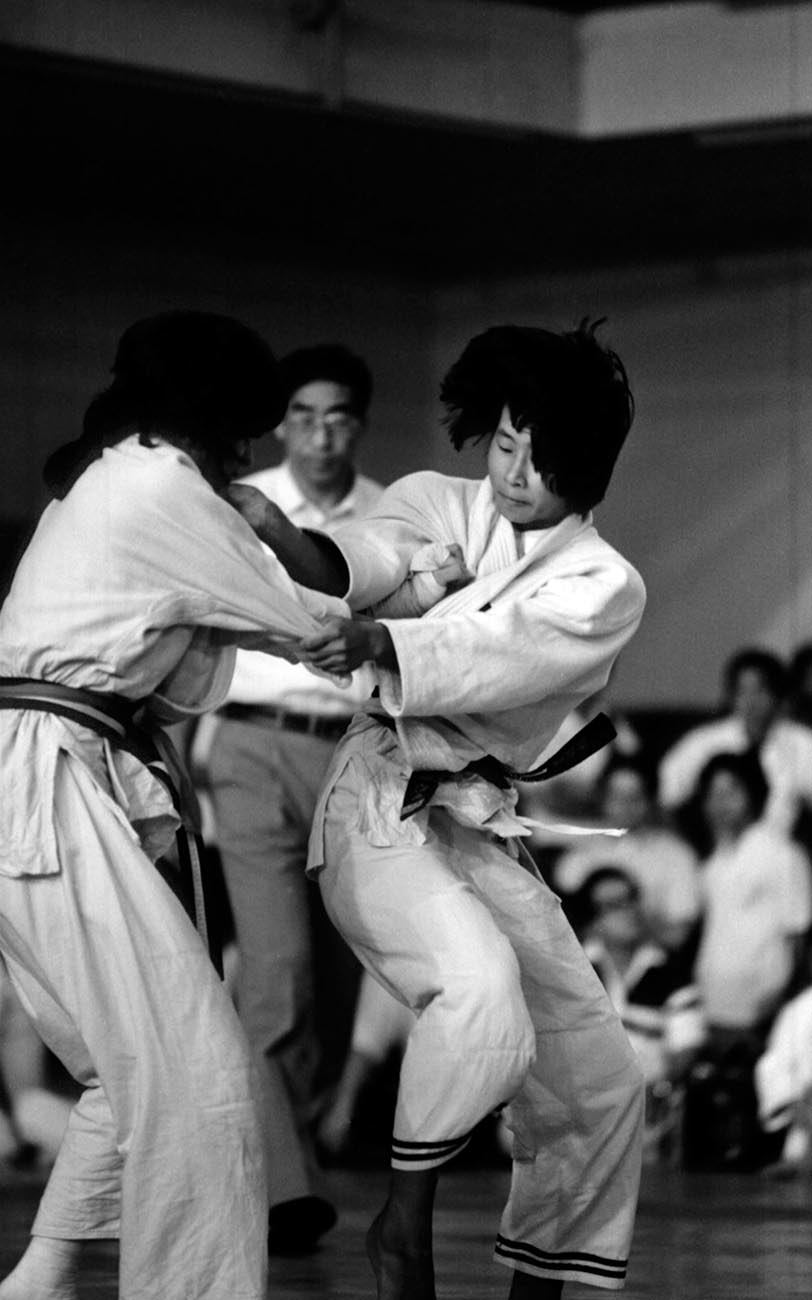

Under Inoue’s leadership, who has combined insights gained from his time abroad with best practices nurtured in Japan, the Japanese men’s judo team earned a medal in all weight divisions at the 2016 Rio Games—the first such feat in 52 years. ©Photo Kishimoto

So since becoming head coach of the national team, I’ve focused my efforts on five major areas. They include the reform—or reexamination—of the judoka mindset, practice routine, and physical training, as well as the reaffirmation of the importance of teamwork and the embrace of scientific research.

For example, most people think that training has to be hard and grueling for it to be effective. That may be true, but competing at the top level requires more than that. You also need to follow a proper diet and get plenty of rest. It’s not enough to simply punish yourself physically.

My policy as head coach has been to develop not just gold medalists but quality athletes as well. They shouldn’t think they can get away with anything as long as they win, which would be inconsistent with the spirit of judo and other martial arts. After all, none of us would be where we are without the support and encouragement of a great number of people. I believe that nurturing quality judoka will make a big contribution to the development of the sport in the years ahead, both in Japan and abroad.

Developing gold medalists who are also quality athletes, says Inoue, is a way of honoring your supporters and contributing to judo’s future. ©Photo Kishimoto

A Pioneering Female Judoka

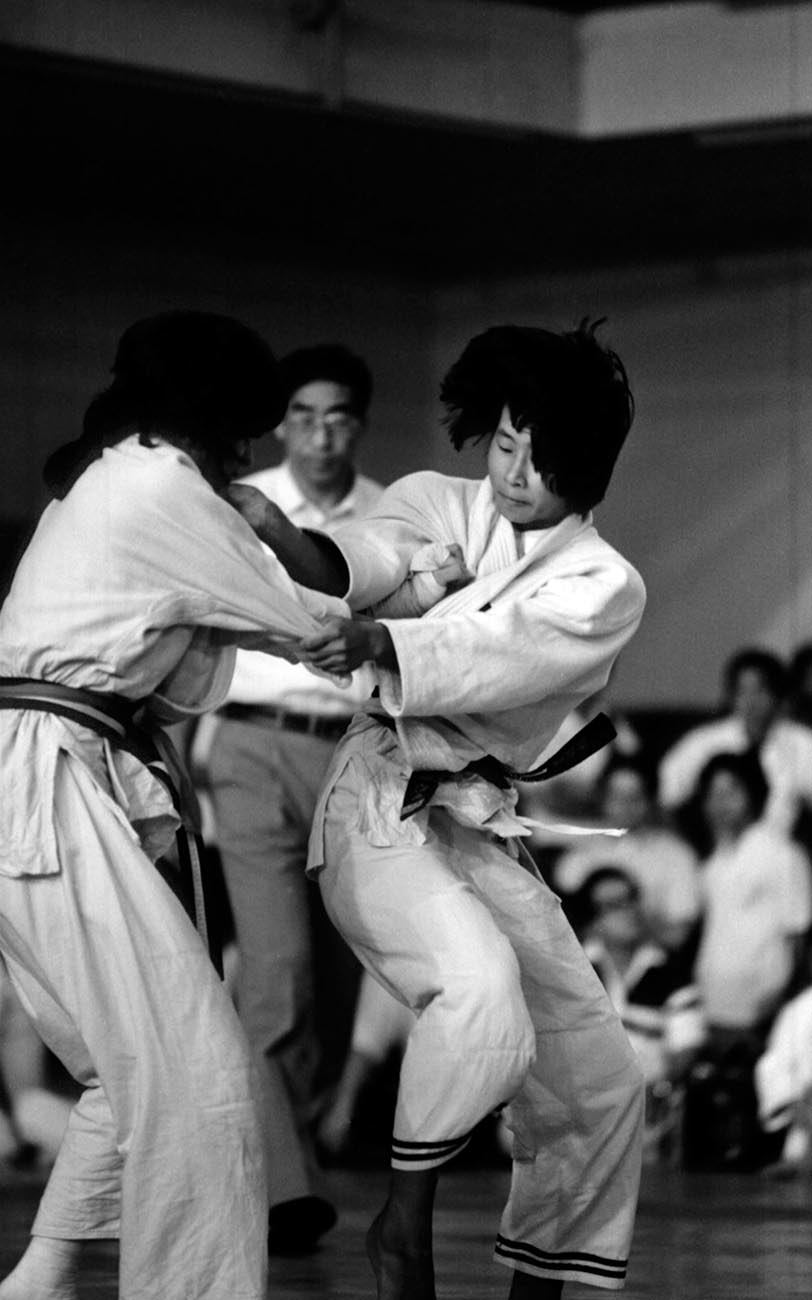

Kaori Yamaguchi, the bronze medalist at the Seoul Games, when women’s judo first became a demonstration event, credits Inoue’s innovations for reviving Japan’s judo fortunes since the 2016 Rio Games. She is no stranger to crossing the gender barrier, having begun judo at the age of six as the only girl in her dojo. In high school and college as well, when few schools had women’s judo teams, she regularly trained with male students.

Kaori Yamaguchi, pictured here in 1980, was undefeated in 10 consecutive All Japan Judo Championships from 1978 to 1987. ©Photo Kishimoto

KAORI YAMAGUCHI: People often assume that I have a feminist mentality since I blazed a path for women in judo, but I got to where I am today not in spite of my male counterparts but because of them. I was coached by men and I trained with them, so I don’t have an axe to grind; I’m very grateful for all they’ve done for me.

I’m really happy to see more women being offered coaching positions, but being female doesn’t automatically make you a better women’s team coach. It’s possible for a male candidate to be more qualified. But at the same time, you don’t want to see a less qualified male getting the job just because he’s friends with powerful people. One way to avoid that would be to adopt a competitive system of selection.

“With more female athletes capturing the spotlight,” comments Yamaguchi, “I hope the ideas women propose will also receive more attention, which would benefit not only sports in general but society at large as well.” ©Photo Kishimoto

I think women need to be better prepared to take on coaching responsibilities should they receive an offer. Many more male judoka actively plan ahead to take on managerial roles, Mr. Inoue being a prime example. He was only 34 and had just returned from Britain when he was named the national team coach. This is a job that puts the destiny of Japanese judo on your shoulders, so I’m sure he had trepidations, but he was obviously ready.

The Tokyo Games could become a major turning point for greater inclusiveness and diversity, opening the door for more women to play a leadership role in all areas of athletic competition. Such an opportunity may not come for another fifty or hundred years, so women need to prepare themselves in anticipation of being called to take on bigger responsibilities.

Promoting Healthy Development

Japanese Olympic Committee President Yasuhiro Yamashita is a hero to many in Japan, winning the gold medal in the open-weight division at the 1984 Los Angeles Games and being bestowed the People’s Honor Award later that year. He has never lost a match against a foreign judoka throughout his career and was unbeaten in 203 consecutive contests, including against Japanese opponents, before his retirement.

The key to developing children, students, and professional athletes, he believes, is for their coaches and teachers to grow and mature as well. In 2013, Yamashita was named by the All Japan Judo Federation to spearhead efforts to eradicate physical and verbal abuse in the sport after 15 members of the women’s national team accused their coaches of harassment and abuse.

YASUHIRO YAMASHITA: Restoring confidence in the judo world following the 2013 abuse scandal will take many years. This is truly ironic, because judo and other martial arts are, by tradition, designed to build character and nurture respect and compassion for others, for which Japanese culture is well known. I hope to do what I can to repair the reputational damage so that judo can make an even bigger contribution to global society in the years ahead.

Abuse occurs when a coach lacks the competence to communicate his or her ideas verbally, points out Yamashita. “Self-improvement is thus essential,” he notes, “for both athletes and coaches.” ©Photo Kishimoto

All successful athletes, not just in judo but in other sports as well, set high goals and push themselves day in and day out to reach them. This requires a lot of creativity and motivation. And these are the qualities I hope we can nurture in younger people, regardless of whether they pursue a career in sports. Athletic careers are very short, after all, so building a foundation of personal resilience can help people deal with setbacks later on in life as well.

In 2006, I established a nonprofit organization called Solidarity of International Judo Education to promote cross-cultural understanding through judo. Its activities included dispatching coaches to foreign countries and inviting both coaches and students to Japan. We provided recycled judo uniforms and tatami mats to developing countries and worked with China and Russia to promote international exchange. Acting on a proposal from the Japanese embassy in Israel, we simultaneously invited judo coaches from both Israel and Palestine for training over a period of nine years. The organization was disbanded in May 2019, after which I became president of the Japanese Olympic Committee, but many of our activities are now being carried out by JUDOs, which was founded by Kosei Inoue.

Yamashita visited children with visual impairments during his trip to South Africa. ©Photo Kishimoto

Judo is built on the philosophy of yawara, in which you “yield” to an opponent’s force and use it against him. I’m also interested in sharing the broader notion of wa, or universal harmony, on which Japanese culture is grounded. I strongly believe that this holds the key to enhancing mutual understanding, and I’m looking forward to working with likeminded people around the world to achieve this goal.

Comments by the speakers (augmented with updates provided by the speakers) translated from excerpts of separate interviews conducted in Japanese on October 24, 2016 (Kosei Inoue), August 29, 2016 (Kaori Yamaguchi), and May 28, 2013 (Yasuhiro Yamashita).