Sticking to the Chosen Path

Yuko Arimori placed second in the marathon at the 1992 Barcelona Games, becoming the first Japanese woman in 64 years to win an Olympic track-and-field medal. She captured the bronze at the Atlanta Games four years later, but perhaps just as memorable as her on-field performance was her comment after her third-place finish: She had overcome injuries and personal trauma to qualify for the Games, so rather than express disappointment at not having improved on her silver medal, she exclaimed that she had poured her heart and soul into the race and that, for the first time in her life, she was ready to congratulate herself for having truly done the best she could.

Yuko Arimori, right, embraces Valentina Yegorova of Russia after their hard-fought marathon at the 1992 Barcelona Games. ©Photo Kishimoto

The comment was a reference to an experience she had during her first year of high school, when she was participating in an inter-prefectural women’s ekiden (relay marathon) in Kyoto. “Folk singer Tomoya Takaishi was a guest at the event and addressed the runners the day before the race with a poem-like speech,” Arimori recalls. “He talked about how impressed he was by the large number of young women who committed themselves to practice so they could be here and that he believed we should all rejoice and take pride in our achievement. Before we seek the applause of others, he told us, we should first congratulate ourselves for overcoming hardships and sticking to our chosen path. He insisted that this was a very important and perfectly natural thing to do and wished us luck the next day.

“I broke down crying when I heard those words,” Arimori adds. I was a substitute on the team and wasn’t actually scheduled to run, so I was disappointed and being hard on myself. But his speech lifted my spirits. At the same time, though, I couldn’t bring myself to take his advice. I knew deep down that I didn’t deserve any praise. So, I wrote his words down in my journal and vowed to save them until the day I could utter them with complete sincerity.

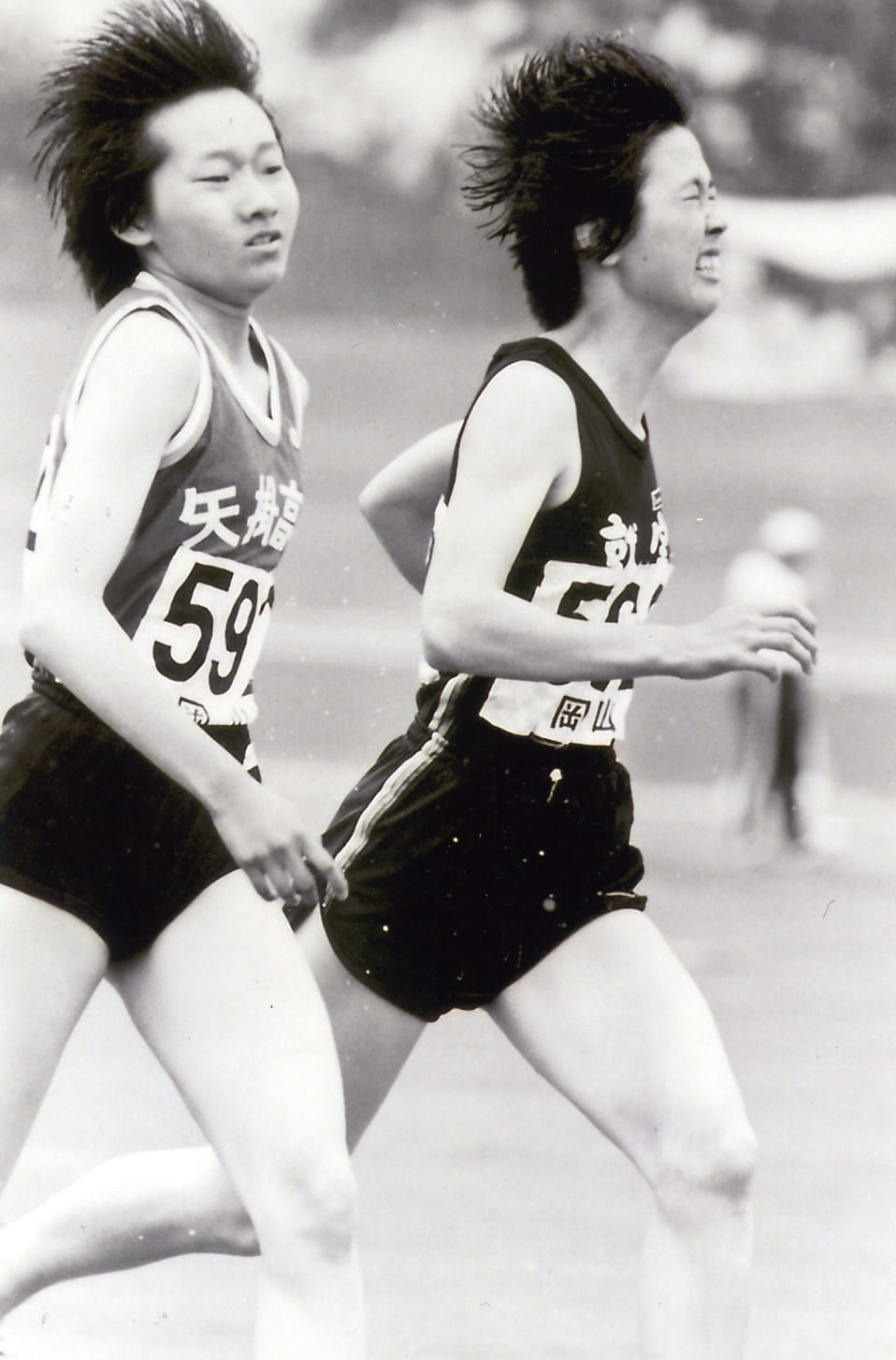

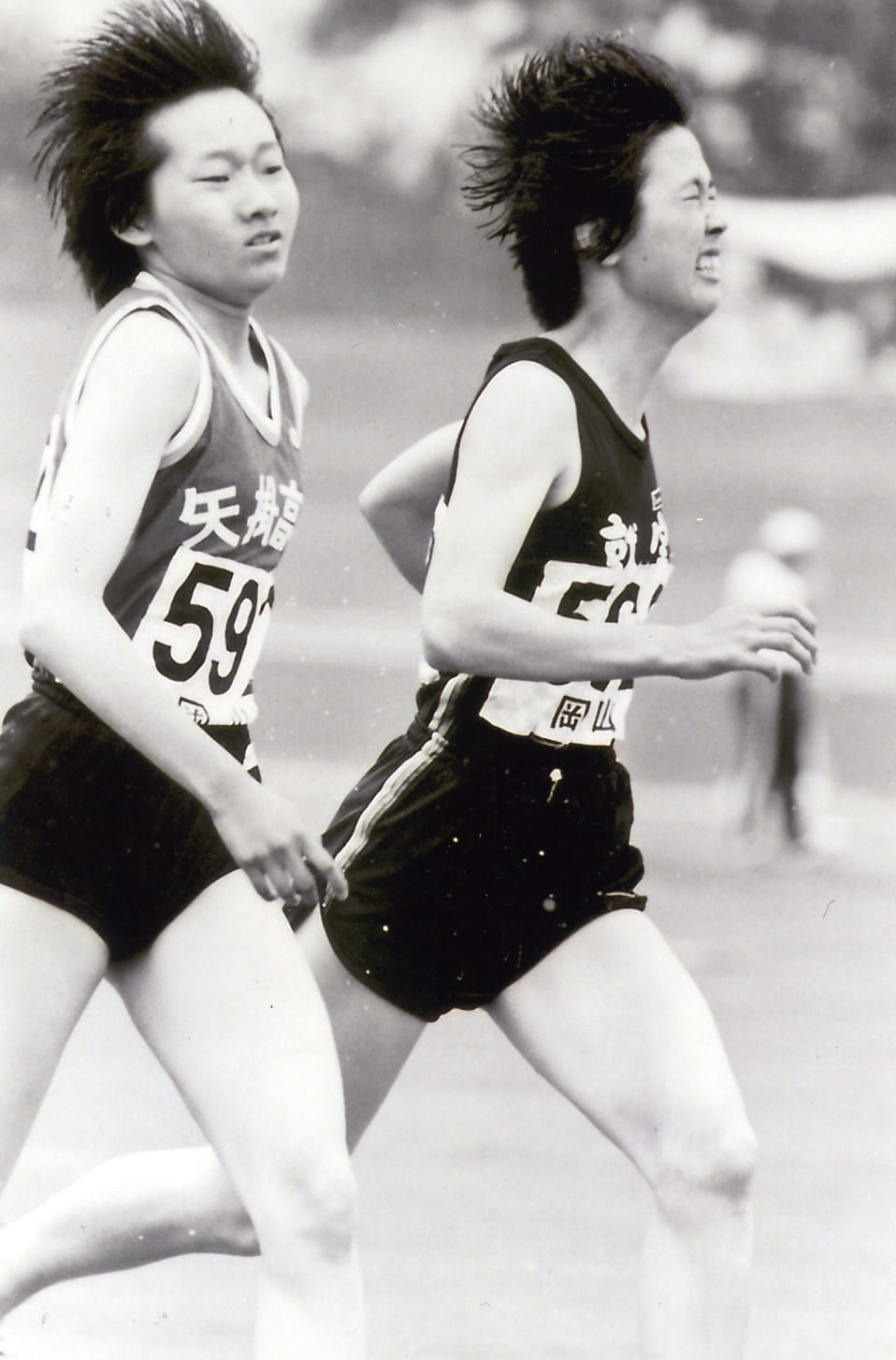

Arimori was a member of her high school track team and was selected three straight years to represent her prefecture at the national women’s ekiden. She was a substitute during all three years, though, and never got a chance to compete. ©Photo Kishimoto

Arimori was not a standout athlete during high school or college, and few corporate track teams were eager to extend her an offer. She nonetheless applied to Recruit Co., a human resources firm that had recently established a competitive running club. The team was then coached by Yoshio Koide, who later gained prominence for developing not only Arimori but also 2000 Sydney gold medalist Naoko Takahashi into top runners.

“I knew I didn’t have the credentials, but I desperately wanted to join the team and pleaded with Mr. Koide to let me in,” Arimori says. “I told him I’d be the first to step down if I wasn’t helping the team. All I wanted was a chance. He couldn’t figure out where my conviction was coming from, given my undistinguished record, but he agreed to take me on with the hope of somehow turning my enthusiasm into tangible results.

Weakness as a Blessing

“It’s not that I was that confident,” she remembers. “I’ve never had a particularly positive frame of mind. In fact, I always seem to be fighting back the fear that my lack of confidence would overwhelm me and hinder my performance. So I make a conscious effort to be strong and to never succumb to despair. This, though, might just be a defense mechanism to hide my weakness.

“I was born with a dislocated hip joint, got hit by dump truck in second grade, and am not very supple. I also realized that I’m not particularly athletic. But I didn’t want to let such negatives get to me. I thought hard about ways to get around my handicaps, devised my own training routine, and really followed through with them until they became second nature. I might not have made it this far if I had a more positive outlook, so my lack of self-confidence was probably a blessing in disguise.”

Arimori’s post-race comment about giving herself credit for doing the best she could was just as memorable as her bronze-medal finish at the Atlanta Games. ©Photo Kishimoto

Listen and Learn

Hammer thrower Koji Murofushi competed in four consecutive Olympics, beginning with the 2000 Sydney Games. The son of a Japanese father and a Romanian mother, he won the gold medal at Athens in 2004 and the bronze at London in 2012. He is now commissioner of the Japan Sports Agency and has held a number of administrative and academic positions, including sports director of the Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Koji Murofushi’s gold medal at the 2004 Athens Games was Japan’s first ever in the hammer throw. ©Photo Kishimoto

Murofushi did not start competing in the hammer throw until the second year of high school, but it was a natural choice, since his father, Shigenobu, too, had been a champion hammer thrower. The elder Murofushi, known as the “Iron Man of Asia,” won 12 Japanese Athletics Championships and five consecutive Asian Athletics Championships, in addition to participating in four Olympic Games. Koji learned from a young age the usefulness of listening to the advice of others and adapting it to develop one’s own style of training.

“I first turned to my father, of course, when I took up the hammer throw in high school,” Murofushi notes. “After I entered college, I also sought the advice of coaches in other sports, like gymnastics and swimming. Interestingly, they all talked about the importance of focusing on the bottom of one’s feet. I was surprised to learn that even in gymnastics, much of which is performed in the air, keeping your attention on your feet is crucial to maintaining your balance during various maneuvers.

Being a good listener, Murofushi says, was a great aid to his development as an athlete. (Photo shows Murofushi and his father-cum-coach at the 2008 Beijing Games.) ©Photo Kishimoto

“If that’s so, I thought, keeping your feet firmly planted must be even much more critical in an event like the hammer throw. I’ve since learned that it’s better not to be too low to the ground, but for a while, I concentrated intensely on grasping the ground with my feet and barely lifting them during the throw.”

Maintaining an Even Keel

Although his compatriots had hoped for a medal, Murofushi finished ninth in his first Olympics at Sydney. “There was a downpour that caused about an hour’s delay during the event. We were all waiting in a tent when a Polish athlete exclaimed gleefully that his best career throw had been in the rain. He went on to win the gold medal, and I realized that rather than being hampered by bad weather, he had turned the situation to his advantage.

“My irritation with the elements further dissipated after reading a book by Japanese literature expert Susumu Nakanishi, who introduced the rich assortment of Japanese words for rain. For example, a different word is used depending on the season in the Man’yoshu, an anthology of poems compiled in the eighth century. I was embarrassed that I had once blamed my poor showing on the weather, and now, when it begins to rain during a match, I simply wonder what word would best describe it.”

The Sydney Games prompted a shift in Murofushi’s thinking about competitive life, leading him to relentlessly pursue change and innovation until retiring as an athlete at age 41. ©Photo Kishimoto

The valuable lesson Murofushi learned in Sydney led to medal-winning performances in Athens and London. “The quality of competitive life can be enhanced with just a small shift in how we perceive things,” Murofushi says. “The way we look at something as mundane as the weather is a perfect example of how little it takes to make our lives much richer.

“The Olympics and Paralympics are showcases for what humans can accomplish when they push themselves to their physical limits. But the energy that drives these athletes comes from within, not without. We can all feel that energy as spectators and also sense that potential in ourselves. These are things that remain in our collective consciousness and will endure, I’m sure, as the intangible assets of the Games.”

Comments by the speakers translated from excerpts of separate interviews conducted in Japanese on June 27, 2013 (Yuko Arimori) and January 17, 2017 (Koji Murofushi).