Pursuing Unbeaten Paths

Miki Matheson (née Matsue) earned four medals—three gold and one silver—in ice sledge speed racing at the 1998 Winter Paralympics in Nagano. She was paralyzed from the waist down in a traffic accident during university, and later moved to the United States to pursue graduate studies at the University of Illinois. There, she was surprised to find facilities that were equally accessible to people with and without disabilities.

Her study abroad proved eye-opening in other ways as well. “One of my professors told me I’d never find what I was looking for by studying what other people had already done,” Matheson says. “If I hoped to become a disability sports coach, I’d have to be creative and open to new ideas, pursuing unbeaten paths to find my own answers. The type and severity of disability differs from person to person, so I realized there was no template or model I could follow.”

Miki Matheson actively promotes Paralympic education in countries around the world and is serving as the deputy chef de mission of the Japanese delegation at Tokyo 2020. ©Photo Kishimoto

Her appreciation of sports as a driver of personal growth and change has deepened over the years, and she is now actively engaged as a global educator, promoting social inclusion by raising awareness of the Paralympic movement and training teachers in Japan and many other countries. In addition to her role as a member of the Education Committee for both the International Paralympic Committee and International Olympic Committee, she serves as project manager of the Promotion and Strategy Department at the Nippon Foundation Paralympic Support Center.

“I want to do what I can to make the Tokyo Paralympics a truly gratifying and memorable event, not just for the athletes but also for everyone who gave their support. There are a lot of people involved in putting the Games together, not just in Tokyo but across the country. We may have different roles, but I hope that the pooling of our efforts will lead to success and that we’ll find joy in being a part of a very meaningful and valuable endeavor.”

Engaging with Life

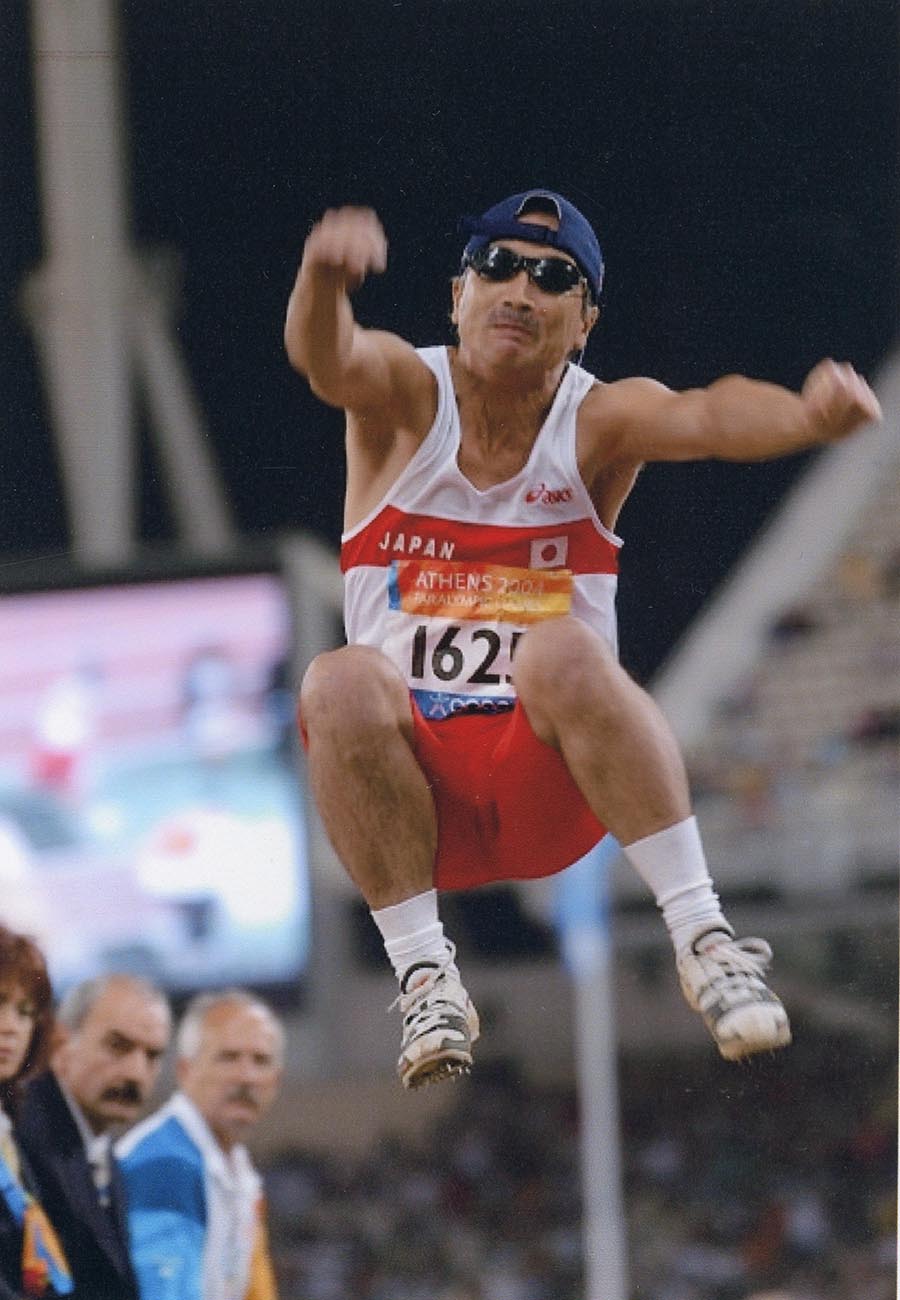

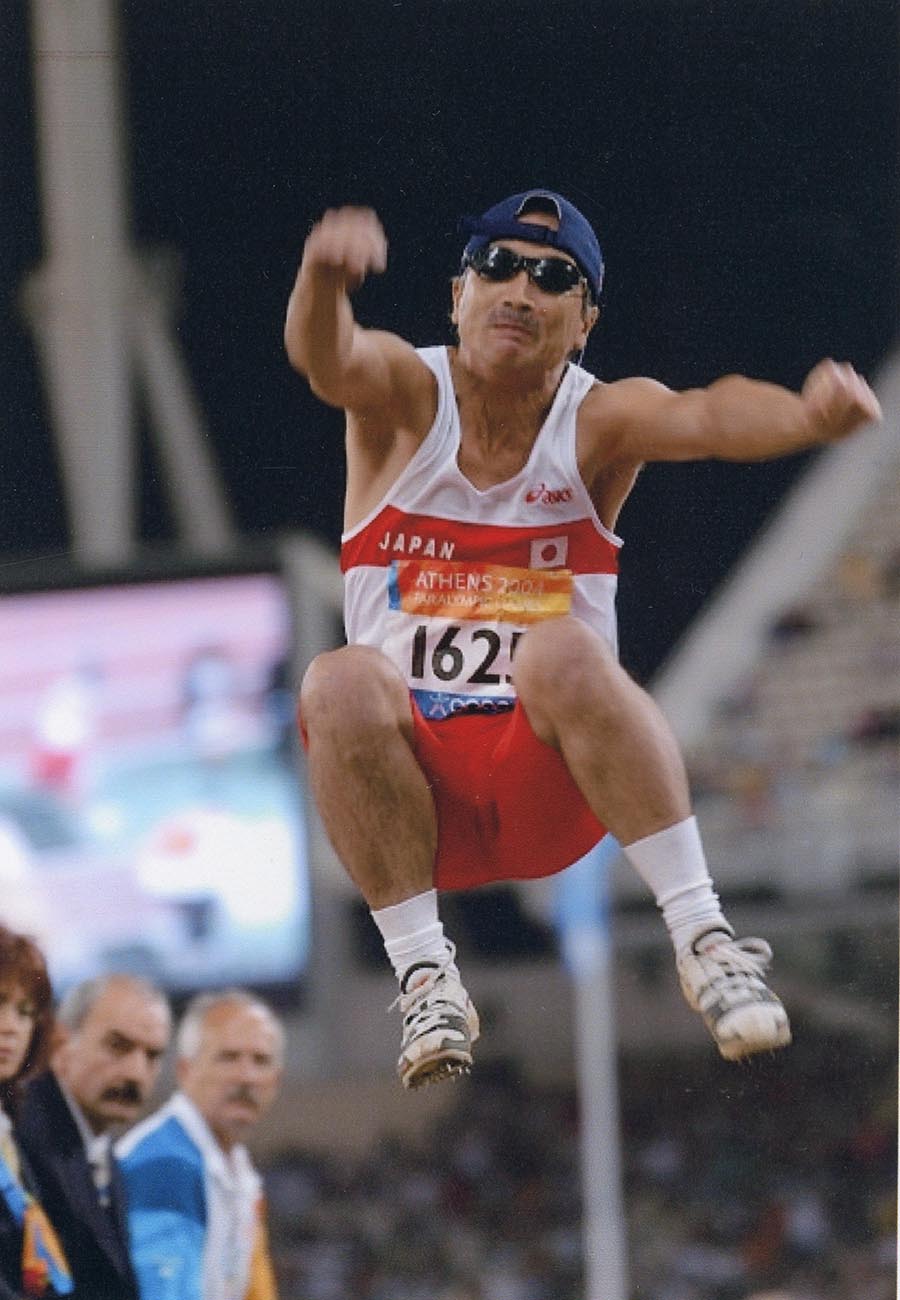

Mineho Ozaki is a Paralympic icon, having participated in seven Games and captured 11 medals, starting with a gold in the visually impaired long jump at the 1984 Paralympics. He remained a dominant figure in the event over the years and set a succession of new world records.

“The four-year cycle of the Paralympic Games was a big motivating factor for me,” Ozaki notes, “giving me a clear goal toward which I could work and also something to look forward to, like visiting the host country and, if I won, hearing the Japanese national anthem at the medal ceremony.”

Ozaki was once featured in a Nike commercial after a producer was moved to capture the height of his jump in a TV ad. “The ad focused first on the jump, and then on my disability, rather than the other way around. I was very happy that the story was told in that order.

Mineho Ozaki has competed in not only the long jump but also the javelin, marathon, and even the “mind sport” Othello. He hopes many more young people will immerse themselves in sports and lead fuller, more enjoyable lives. ©Photo Kishimoto

“I get the impression that kids today have fewer opportunities to really enjoy themselves or to work hard and get rewarded for it. Through sports, you can learn how much effort you need to make to reach a certain goal, motivating you to try harder and making you more engaged in life. There are practical benefits as well, of course, like increasing your appetite and giving you a quicker mind. I hope many more younger people, including those with disabilities, will avail themselves of the opportunities sports offers to enrich their lives.”

The Qualities of a Paralympian

Tomoya Ito was 34 and in the midst of an entrepreneurial career as the founding manager of a staffing agency when he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Instead of lapsing into despair, he set his sights on becoming a Paralympian after he mistakenly ordered a racing wheelchair. He talked his way into being allowed to train for and compete in the wheelchair marathon while still in the hospital, despite medical advice that symptoms could get worse when body temperatures rise, and worked to become one of Japan’s top athletes in the event.

“Compared to prominent, able-bodied athletes, their lesser-known para-counterparts are often forced to make great sacrifices,” comments Ito. “This is a situation that needs to be rectified, so I decided to lobby for change. I feel very strongly about this issue, and I’ve made it one of my life goals to elevate the status of para-sports.”

In Ito’s Paralympics debut in 2004 at Athens, his chair toppled over during the 1,500-meter race and crashed into another athlete. “I crawled about five meters to apologize to my fellow racer,” Ito recalls, “but instead of being upset, he was very generous, saying it was an honor just being able to race with me and that the contest was really to see who was the greatest guy in the world. That touched me, and I realized that it wasn’t enough just to be fast. A true Paralympian is virtuous, kind, and warmhearted. He had won the gold medal in 2000 at Sydney, but he died just two years later. I’ve tried to live by his words ever since then and to be worthy of being called a Paralympian.”

Ito won the gold medal in the 400-meter and 800-meter races at the 2008 Games in Beijing and took home the silver in three contests four years later in London. He subsequently retired at one point but returned to competition in 2017. He competed in the 400-meter race at Tokyo 2020 despite being classified just before the Games as T53, a lighter disability class than in previous contests.

Tomoya Ito was already 45 when he set new world records en route to winning gold medals in the 400-meter and 800-meter wheelchair races (T52) at the 2008 Beijing Games. ©Photo Kishimoto

Ito sees the Paralympic movement as helping highlight the need for universal design. He feels, though, that efforts to enhance ease of access should focus on eliminating not just physical barriers but social and psychological ones as well. “This is an issue that will become increasingly critical with the aging of the Japanese society. At the same time, if the Paralympics are to survive into the future, they must come to be seen like any other sporting event, not as a ‘special’ showcase for people with disabilities.”

Tomoya Ito recorded his personal best in the 400-meter wheelchair race (T53) at Tokyo 2020. ©Photo Kishimoto

Sports as an Integral Part of Life

Wakako Tsuchida has participated in eight Summer and Winter Paralympics, starting with the 1994 Games in Lillehammer. At Tokyo 2020, she was selected to compete in both the marathon and her first para-triathlon. She has earned seven medals to date and was the first Japanese para-athlete to win both a summer and winter gold.

"The announcement that the Tokyo Paralympics would be postponed by a year caught me off guard, and having to reschedule everything was quite an ordeal, given the large number of people involved in helping me train. Many activities had to be curtailed when a state of emergency was declared in April 2020, but these developments might have been a blessing in disguise, giving me an extra year to work on my weak areas.

Wakako Tsuchida, who at age 46 competed in her first para-triathlon at Tokyo 2020—her eighth Paralympic Games—was a torch runner during the Olympic opening ceremony in July. ©Photo Kishimoto

“Sports has been an integral part of my life,” Tsuchida says, “and has helped me to grow as a person.” She feels strongly that athletes must continue striving toward higher levels of attainment for the Paralympic Games to gain a broader public following.

“As important as sports is to me, the COVID-19 pandemic has taught me that it’s secondary to life and world peace, which are precious above all else. I do hope that the Games in Tokyo and thereafter will offer solace and peace of mind to people around the world in these very difficult times. And I also hope that the Paralympics will serve as an impetus for the building of a more inclusive society.”

Comments by the speakers translated from excerpts of separate interviews conducted in Japanese on January 30, 2017 (Miki Matheson), December 11, 2015 (Mineho Ozaki), March 4, 2015 (Tomoya Ito), and January 21, 2021 (Wakako Tsuchida).