Sports Clubs as Places to Learn and Grow

While designed to encourage sports participation for people of all ages and skill levels, community-based sports clubs also play an important role in developing the next generation of competitive athletes. Some sports clubs in Europe have been around for over a century, but most of the approximately 3,000 clubs in Japan were established following the 1964 Tokyo Games.

The first Japanese sports club to be launched as a corporation was Central Sports Co., Ltd., founded in 1969 (and incorporated the following year) by swimmer Tadaharu Goto—who competed in the men’s 4 × 100m freestyle relay at the 1964 Games—along with gymnasts Takashi and Kiyoko Ono and Yukio Endo.

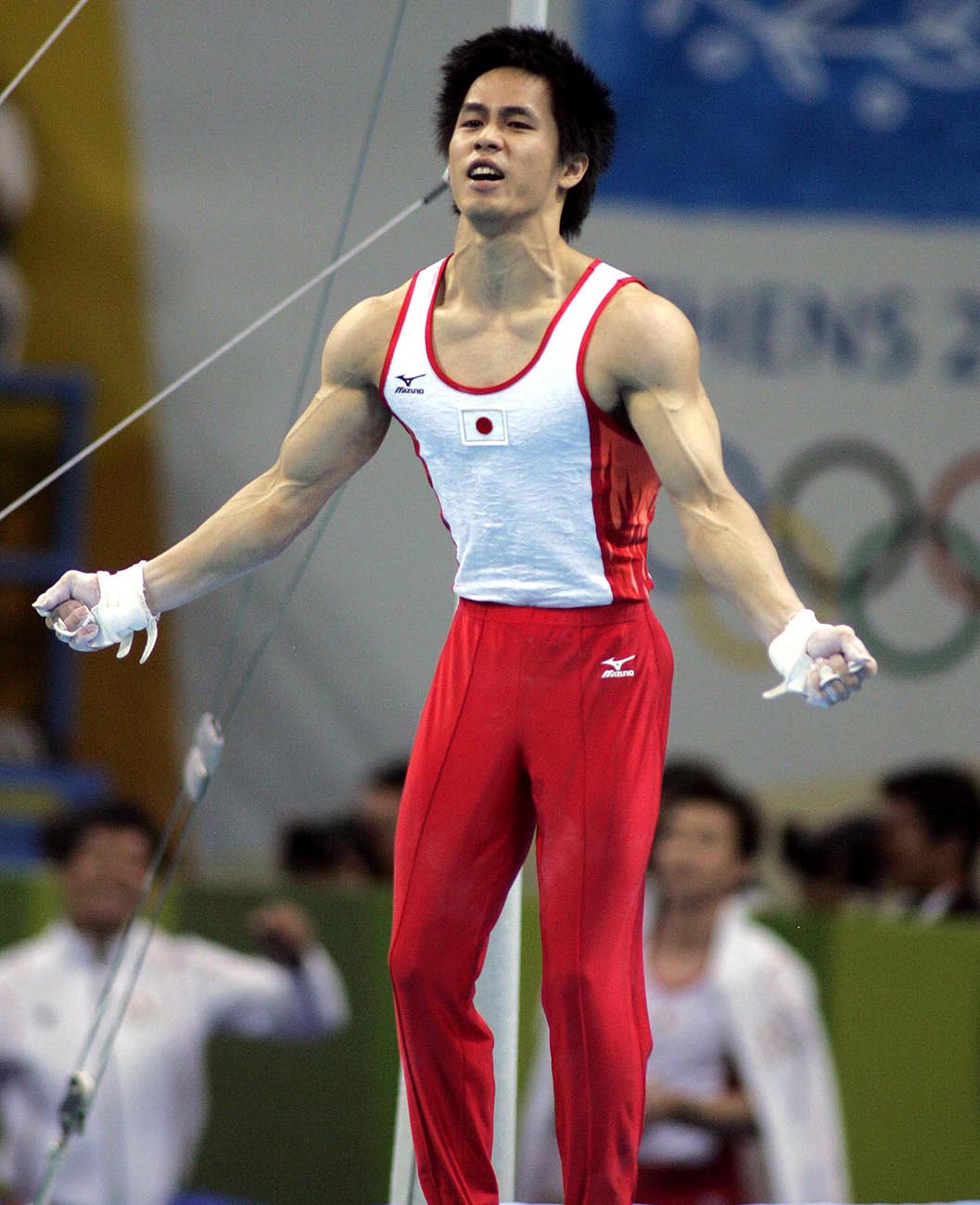

Central Sports has produced a number of Olympic gold medalists. Daichi Suzuki won the 100m backstroke at Seoul, while Hiroyuki Tomita and Takehiro Kashima were members of the men’s all-around gymnastics team that triumphed at Athens. And among the Tokyo 2020 participants were swimmer Katsuhiro Matsumoto (200m freestyle) and gymnasts Kazuma Kaya, Wataru Tanigawa, and Hitomi Hatakeda.

Central Sports has spawned many top athletes, including Olympic gold medalists like swimmer Daichi Suzuki and gymnast Hiroyuki Tomita. ©Photo Kishimoto

Sports, Goto believes, can play a big role in promoting mental and emotional health as well. “Sports clubs offer a unique learning environment,” he notes. “They can encourage personal growth as you test and challenge yourself, and they also help teach schoolchildren to follow rules and work with others. If you acquire these skills when you’re young, they’ll become vital assets for you even after you leave sports and move on in life.”

Instilling Good Habits

The key to nurturing top athletes is to start young, believes Yoshihito Miyazaki, executive director and head of development of the Japan Table Tennis Association. He was a member of Japan’s national team at the Seoul Games in 1988 and was invited to become its head coach in 2001.

“My condition for accepting the offer was that the association create a national team at the grade-school level,” Miyazaki recalls, “and this is what we did after I became head coach.” To his disappointment, however, almost none of the best young athletes developed into world-class competitors.

“Most of the pre-teen players relied on a strategy of winning points with a backspin serve that was popular at the time. This worked against junior opponents, but after reaching the senior level, there were plenty of players who could return trick serves. I realized that these players wouldn’t stand a chance in international competition as long as they adhered to this approach.”

Rather than encourage a technique that was effective only against younger rivals, Miyazaki focused on developing the skills players would need to compete at the top level as they matured. He helped establish the Japan Olympic Committee’s national training center and headed the JOC Elite Academy, a training facility with residential quarters for promising young athletes.

Tokyo 2020 table tennis medalists Tomokazu Harimoto and Miu Hirano underwent training at the JOC Elite Academy. (Photo shows young athletes practicing at the academy in 2014.) ©Photo Kishimoto

“The academy wasn’t just focused on improving table tennis and other athletic skills,” he points out. “We provided a total educational experience to foster a positive mental attitude. For instance, students were taught to line their shoes neatly, to follow a healthy and balanced diet, and to get plenty of sleep. A positive attitude leads to better concentration during practice and ultimately to better results in competition. Mental toughness can often be the difference between a win or loss in a closely contested match.

“I’m now working to ensure that these kids also get adequate schooling. Those who join the academy have to take time off from classes to participate in tournaments or travel far to play other teams. Some of our top players can spend only 40 days a year in a classroom. I’m hoping that a school can be set up within the national training center for such kids. The complex is under the jurisdiction of the education ministry, so I’m sure they can find a way to provide good schooling for our young athletes.”

Secondary Schools as Training Grounds

Shigetaka Mori is president of the Japan Rugby Football Union and was Japan’s leading center back as a player. After retiring at age 30, he spent many years as coach at the high school in Fukuoka from which he graduated, leading his team to the National High School Rugby Tournament in 2010.

Middle and high school sports teams are important training grounds for those who go on to compete at the top level. Sasakawa Sports Foundation data shows that in 2019, some 62% of all secondary students in Japan engaged in sports as an extracurricular activity.

“I remember visiting New Zealand for the first time as a member of the Japanese national team and being shocked by what I saw,” Mori reminisces. “Rugby was an integral part of life in that country, and I thought there was no way we could win against such a team. I wanted to share this insight with our young players, and that’s why I took them on a tour of New Zealand. I wanted them to get a firsthand feel for the improvements we’d have to make for Japan to even have a chance of winning at international tournaments.”

As Fukuoka High School rugby coach, Shigetaka Mori led his public-school team to New Zealand, giving students a taste of high-level competition while they were still young. (Photo courtesy of Shigetaka Mori)

High school sports clubs have come under attack in recent years as issues like physical punishment by instructors and bullying among the players have come to light. “Times have changed, and it’s not easy being a high school coach these days. If I were still coaching, my style might prompt some people to accuse me of power harassment,” Mori admits. “I could be a tough drill sergeant at times, but the players could see I was giving them 100 percent, and they responded in kind.

“Forcing players to run just for the sake of it or as a form of punishment can never be justified. But there are times when you have to be hard on the players. By keeping their best interests at heart, you can instill discipline and good manners. And I’m sure these things will benefit them later in life.”

Parental Guidance

Many of Japan’s medalists received their initial training from their parents, among the most notable being Saori Yoshida, a legendary freestyle wrestler who claimed 16 competitive world titles, including 3 Olympic gold medals, while winning 206 straight matches.

“Wrestling was compulsory in our family when I was growing up,” notes Yoshida, whose father—a former national champion—made wrestling a part of the daily regimen for her and her two elder brothers. “I wanted to play with my friends and often thought about quitting,” she says, “but in our family, my father’s word was final, and there was no way I could disobey him.”

Yoshida’s attitude toward wrestling underwent a sea change in eighth grade after watching Ryoko Tamura (now Tani)—considered the best female judoka ever—competing at the 1996 Atlanta Games. “There was an air of invincibility about her, and I remember wanting to be just as strong as she was.” From then on, she no longer needed her father’s prodding to practice.

“My father used to exhort me to tackle my opponents, which is the ultimate form of attack,” she remembers. “Those who can tackle, he would always say, ultimately conquer the world. He insisted that I always stay on the offensive and would chew me out if I didn’t—even if I won the match. That was his criterion for how well I fought. He would give me a pat on the back when I lost, though, if I kept attacking with an onslaught of moves.”

Saori Yoshida, taught by her father to constantly be on the attack, makes a high-speed tackle at the 2008 Beijing Games. ©Photo Kishimoto

It was also Yoshida’s father who decided which high school and college she would attend. “That was pretty frustrating at the time, but looking back, I’m glad I followed through with his decisions. I have no regrets, and if I had to do it all over again, I wouldn’t change a thing. I credit my success to my father, and I’m really happy I listened to him.”

Comments by the speakers translated from excerpts of separate interviews conducted in Japanese on August 21, 2013 (Tadaharu Goto), February 29, 2017 (Yoshihito Miyazaki), October 15, 2018 (Shigetaka Mori), and February 21, 2017 (Saori Yoshida).