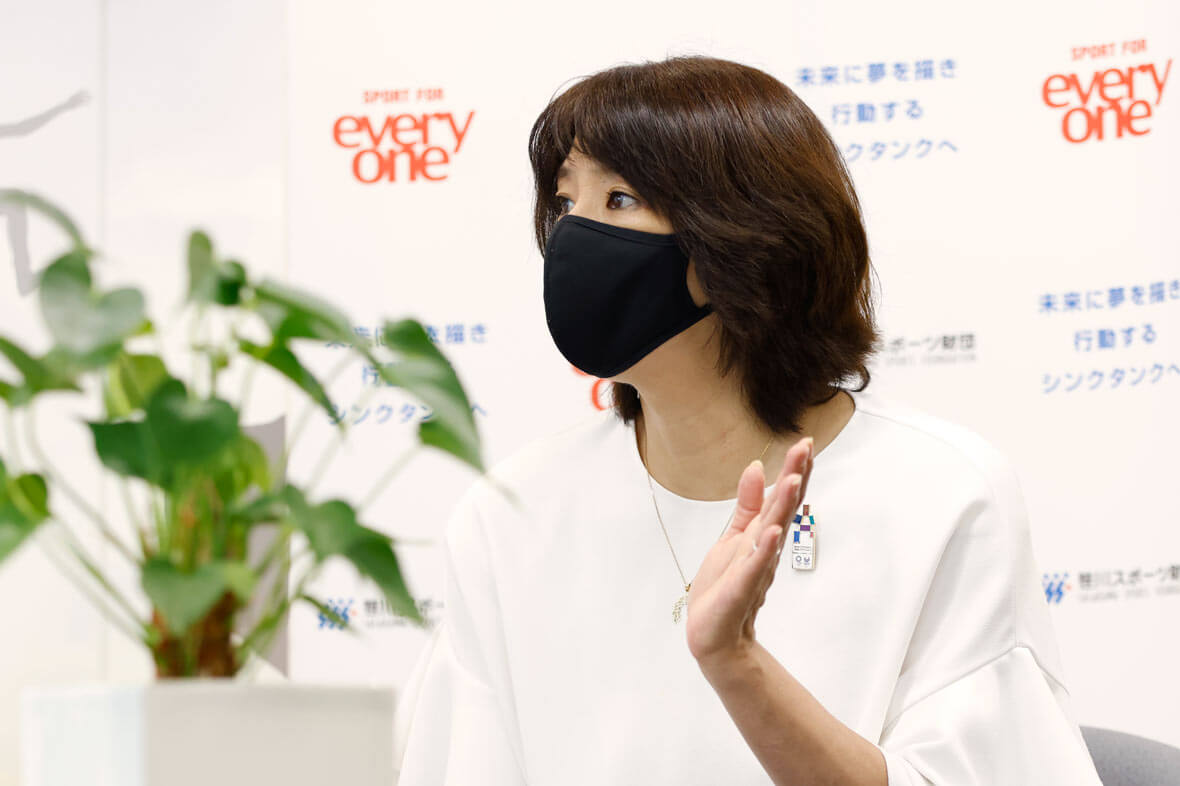

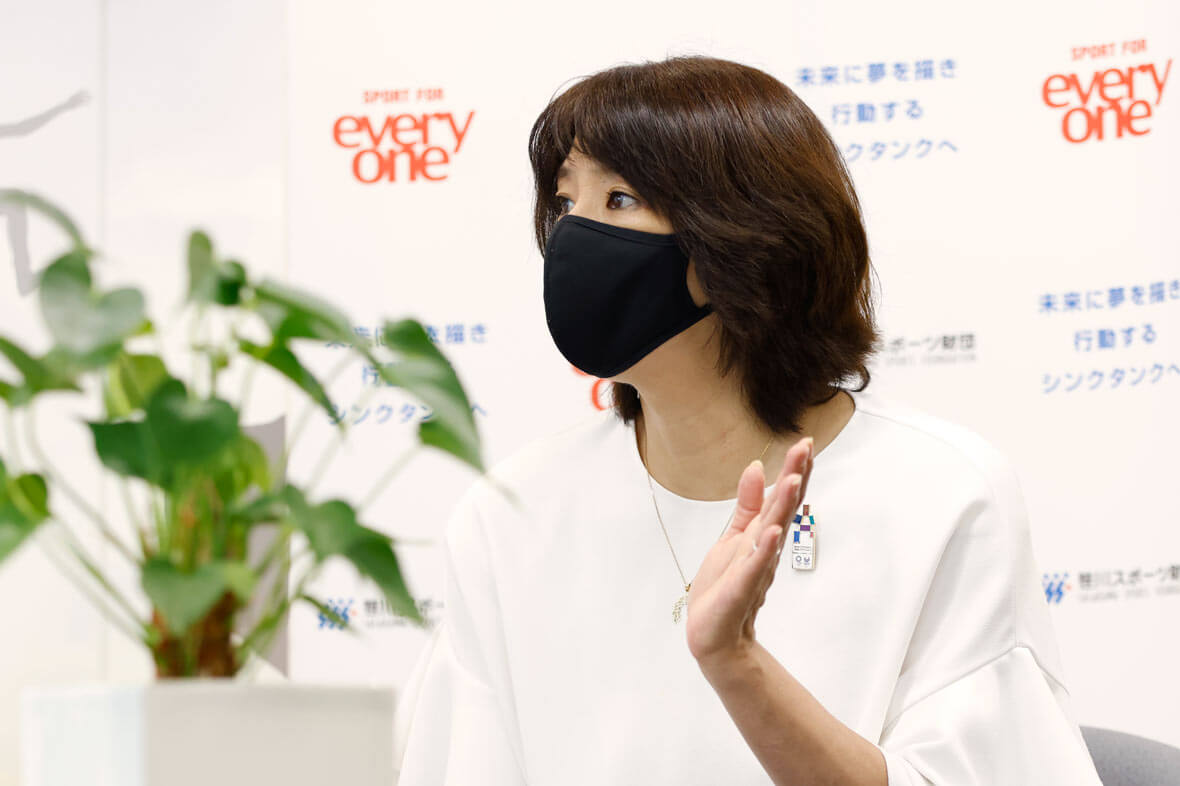

SSF: Can you describe how Tokyo’s bid to host the 2020 Games evolved in the face of shifting public opinion?

MIKAKO KOTANI: As we were contemplating another bid after our attempt to host the 2016 Games ended unsuccessfully, the March 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake struck and created a national emergency. Some argued that recovering from the disaster required the country’s full attention and that this was no time to be thinking about the Olympics and Paralympics.

When I visited the affected areas, though, many people came up to me to offer their support for our candidacy. Additional momentum came from the outstanding performance of Japanese athletes at the 2012 London Games, who won a record 38 medals. There was an outpouring of enthusiasm, as demonstrated by the approximately 500,000 people who packed the streets of central Tokyo for a post-Olympic parade by the medalists. I believe this had a great impact on athletes, as many subsequently openly declared their support and cooperation in the bidding process for the 2020 Games.

A parade through the streets of central Tokyo featuring London 2012 medalists. ©Photo Kishimoto

SSF: That said, many people still harbored doubts about hosting the Games in the midst of a pandemic, and there was no shortage of media coverage fueling their anxiety.

KOTANI: Our top priority was to ensure that the Games were safe and secure, and this entailed establishing strict rules in our Playbooks.* We had to explain the restrictions many times to the various international federations, as well as competition officials and judges, and thankfully, everyone agreed to abide by them. As COVID cases in Japan continued to rise, however, we were facing public opinion headwinds, and this made it very hard to build momentum for the Games domestically.

*The rulebooks, developed by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the International Paralympic Committee (IPC), and the Tokyo 2020 Organizing Committee, outline COVID-related guidance and other rules and responsibilities of all Games stakeholders.

Dealing with the criticism wasn’t easy for me personally, but it was much harder for the athletes. It pained me to see them hesitate to say they wanted to compete in the Games and feel they might be criticized for their comments. Such anxiety was shared by those on the organizing committee as well, prompting some to remove their committee badges when leaving the office. It was a very difficult time for everyone involved.

Kotani, center, visits an Olympic venue during Tokyo 2020. ©Photo Kishimoto

SSF: What were some of the restrictions that the pandemic forced on athletes and officials?

KOTANI: As a rule, athletes and staff were allowed to stay in the Olympic and Paralympic Village only five days before and two days after their events. Their areas of activity were limited to the Village, event venues, and practice sites, and they were also subject to daily PCR tests. We invited only the minimum number of officials and referees required for the staging of the Games.

As harsh as these rules may seem, athletes could at least buy souvenirs in the Village and sample a wide variety of dishes in the cafeteria. Federation officials, on the other hand, were largely confined to their hotel rooms, and some had to rely on room service for all their meals.

Even under such stressful circumstances, officials told me that they were proud to be part of an event that, due to unprecedented challenges, had great social and historical significance. I was very grateful for such remarks and became even more committed to doing everything in our power to ensure the safety and security of the Games.

SSF: How did you seek to achieve “Unity in Diversity,” which was one of the core concepts of the Vision for the 2020 Games?

KOTANI: One expression of this concept was the Olympic oath at the opening ceremony, which was conducted in a gender-equal manner by pairs of athletes, coaches, and referees. We also added mixed doubles in table tennis and mixed teams in judo, doubling the number of mixed events from 9 at the 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro to 18. And while it was customary in many events for the men’s final to come after the women’s final, we reversed the order in five events. We also asked people in wheelchairs and those with visual impairments to serve as medal tray bearers and victory bouquet carriers at the awards ceremony. We were able to create an inclusive environment featuring great diversity in terms of age, gender, and physical appearance.

Jun Mizutani, left, and Mima Ito of Japan show their gold medals in table tennis mixed doubles, an event held for the first time at the Tokyo Games. ©Photo Kishimoto

Many sports managers responsible for preparing the various Olympic venues volunteered to help out at the Paralympics as well. Such sharing of Olympic and Paralympic organizational resources is an ideal way of achieving “unity,” since many national para-sports federations are quite small and understaffed.

While we were able to make some progress regarding gender equality among athletes, perhaps an even bigger challenge is raising the share of women leaders in athletic organizations and the international political arena. We have a long way to go, but my impression is that most sports organizations now at least recognize the need for change.

SSF: How have you applied your experiences as an Olympic swimmer in Seoul and Barcelona to your subsequent career?

KOTANI: I was overjoyed to win two bronze medals in the solo and duet events in Seoul. In Barcelona four years later, I was a reserve, but I knew that some people were advocating that I be allowed to compete, given my performance at the previous Games. The selection was ultimately made on the morning of the final, and the two swimmers considered most likely to win a medal were chosen.

Needless to say, I was really disappointed that I wasn’t among the two, and it was frustrating not being able to contribute, but in hindsight this proved to be a very important lesson for me, and I’m glad that I got a chance to experience just how rigorous competitive sports can be. The strength it takes to overcome such setbacks is what makes the athletes shine and why it can be so exciting to watch them perform. The competition is tough, but that’s what makes the Olympics so special. I owe the fact that I’m still involved in sports to that experience, and I’m now grateful that I wasn’t chosen.

©Photo Kishimoto

SSF: Based on what you learned from Tokyo 2020, do you have any thoughts on how future Games should be staged?

KOTANI: The pandemic forced us to streamline our operations in 52 areas, such as minimizing structures that would need to be torn down after the Games and reducing the number of staff. The result was one of the most compact Games in recent memory. This had no adverse impact on the quality of competition, though, as evidenced by the number of new world records. A Kyodo News poll conducted after the Games revealed that 62.9% and 69.8% of the Japanese public, respectively, were glad that the Olympics and Paralympics were held.

I think these facts demonstrate that our efforts to showcase the essence of the Olympic and Paralympic Games—namely, the power of sports—were largely successful. We were able to show that bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better, and in that sense, our compact and more sustainable “Tokyo Model” could become the standard for Olympic and Paralympic Games of the future.

Translated from an interview conducted in Japanese on September 30, 2021.